Before watching the movie:

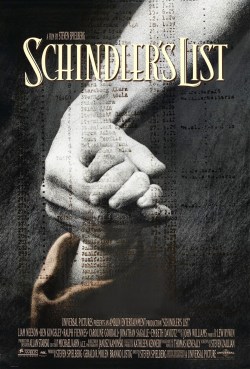

There are probably other films that I’ll remember later that are at least comparable as movies I’ve felt like I had to review at some point, but this one has always been basically the most “must-review” movie since the beginning.

I understand that this is a dramatization of a real story of a factory owner using his privilege to get Jews out of the Holocaust. It is also definitely going to be a Hollywood “The Holocaust was Bad” movie. Every movie condemning the Holocaust is to its own degree earnest and moving, but the lesson has been taught over and over and at this point it’s become a “Best Picture Oscar please” button while the West is becoming more enamored with racism and fascism anyway.

After watching the movie:

Soon after Nazi Germany conquers and annexes Poland, capitalist Oskar Schindler arrives in Krakow with a plan to use the war as the missing element his previous failed businesses lacked. He comes to local Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern with a plan: Stern will connect him with Jewish investors who are no longer allowed to own businesses, they give him the money to buy a formerly Jewish-owned enamelware factory, which he’ll pay back in goods under the table, and Stern will run the company, leaving Schindler’s role to be to schmooze with the important people who can make the big deals and to get filthy stinking rich off the whole thing. Under Nazi rule, Jewish labor (slave labor purchased from the German government) costs less than hiring non-Jewish Poles, so why would he hire Poles? Immediately, Stern starts using his position as Schindler’s manager to hire the neediest ghetto residents into Essential Worker positions they may not be qualified for, and Shindler is a little irritated by the inefficiency but much more angered by arbitrary Nazi orders and summary executions costing him workers, and chews out his high ranking Nazi friends about every time his workers are pulled to other projects or just casually murdered. Schindler’s factory starts to get a reputation among the Jews that he’s angered to hear about, but as a human being can’t help but start to lean into once the thought is in his head. When the workforce from the Krakow ghetto is pulled into the new Płaszów work camp and Schindler finds his factory suddenly empty, he goes to camp commandant Göth furious about his workers being taken from him and is offered the chance to build a new factory inside the camp as a sub-camp under his own control, for a price. Working inside the camp now, Schindler begins to truly recognize the inhumanity of the situation and starts actively working against it, with small suggestions to officers about the power of showing mercy, with bluster and his own authority and rights within German law, and with appeals to his friends in high places if necessary. But as the Nazi regime begins to move from using the Jews as slaves to outright extermination, Shindler begins to realize that he has one more resource that can do the most good against this horror.

I came into this with the impression that Schindler had a master plan almost from the beginning. However, I found it much more interesting to watch his evolution from complete mercenary capitalist who just doesn’t care about the Jews any more or less than any other person but knows a good business opportunity. We ee his change creep up over years of working closely with Jewish laborers and seeing the injustices done to them by the regime that gave him his opportunity, slowly getting dragged into using everything he’s built to do the most good. Schindler was so interesting in every scene (no doubt helped along by Liam Neeson’s charisma) that it unfortunately gave me an extra sense of the movie being distracted from the story whenever it left him and his family and returned to the brutality of the Holocaust. I was worried about this effect going in, of lionizing the Good Nazi over the suffering of the people he’s righteously saving, but the film does its best to counter this by giving us several Krakow Jews to get to know, and extended sequences from their perspectives.

There have been many movies about the Holocaust, but I don’t think I’ve seen as much of the raw violence depicted. Dozens of people are unceremoniously killed on camera, and I feel that serves the purpose of making the brutality present and real in a way that is not often captured. On the other hand, while there are a handful of sequences where explicit nudity is used to portray the dehumanization of the oppressed, there are many more instances where it seems like the point was to ogle a sexy lady, as it adds nothing narratively that wouldn’t be served by a more covered-up staging.

This is one of the longest movies I’ve reviewed, certainly of any selections of the last few years at over three hours long. Maybe some older musicals have eclipsed that but not by much. The black and white cinematography (aside from a few highly as symbolic moments) never gets in the way of the compelling scenes, from scheming and dealing to the final scenes as the war ended and the flash forward to the modern day with the real Schindler Jews that brings the weight of all the grief and gratitude for the thousand and change that were spared and the millions that couldn’t be saved. In so many Holocaust stories the end is just “and then they died but somebody learned a lesson about humanity”, but this is a story about the audacity to make a difference, and hope actually vindicated in a truly hopeless time.

Graphic violence was never necessary for me to understand the evil of the Holocaust. I would hope that anyone can be made to recognize the monstrosity of stripping people of their rights, property, wealth, dignity, humanity, and lives due to their heritage. The rhetoric of the fascists explicitly tries to sever the connection between the Other and personhood. It is evil because they are people, not because of preferring the oppressed race over others. Never again, to anyone, because no one deserves to have done to them what you wouldn’t want done to you. There are too many (mostly in the leadership of the state of Israel and that of its allies) whose feeling is more along the lines of “if we can pay it forward it will ensure it will never again happen to us.” However, I do hope that for those that it is necessary, the humanization of getting to know these people and their story, and seeing someone who considers himself non-partisan become radicalized allows those who need help seeing past their privilege to do so.