Before watching the movie:

While this movie’s copyright has not expired, the book is as of this year in the public domain (and so is the original English translation, which I hadn’t realized came so quickly after). I’ve considered coming to this one a few times when an antiwar story would have topical currency, but I never made it all the way.

I mostly know only in vague terms how directly this story illustrates the hell and futility of war, aside from having heard of the scene where a protagonist kills an enemy soldier in a foxhole and, on examining the dead man’s pockets, realizes just how relatably human the “enemy” really is.

After watching the movie:

In a German town in the early days of the Great War, Professor Kantorek passionately speaks to his students about how he doesn’t expect them to all go enlist as a group as other classes of boys have, but when you think of the honor, glory, and duty of defending the Fatherland, really why haven’t the lot of them already joined up? And so the entire class, led by Paul Baumer, do in fact all go out together and join up as the Second Company, with dreams of glory, excitement, and heroism. Any illusions they had are promptly crushed by their basic training, led by Corporal Himmelstoss, a man they knew as their town’s jovial postman, now turned into an unrecognizable bully. Their training complete, they get shipped by train to the Front, and one of them gets killed on the way to the post, where there is no food and no welcome from the older veterans waiting for them. In the war zone, they find little for them but death, dismissal, and lack of support and supplies. They alternate shooting from trenches and charging the battlefield with hiding in the bunker slowly going mad while the enemy drops relentless barrages on them. And nobody really understands what they’re fighting for anyway.

Something about the way this story was structured (and it’s highly episodic) made it difficult for me to pick out a more specific protagonist than “the company” until they had thinned out about halfway through. Even though Paul was called out as the “leader” of the class at the very beginning, I didn’t really have a sense of him as the focus until he was the only one who cared more about the dying classmate/comrade than about the boy’s exquisite boots. From that time, the focus turned from the more immediate and obvious demoralization of wartime to more introspective revelations that need a central character to get in the head of.

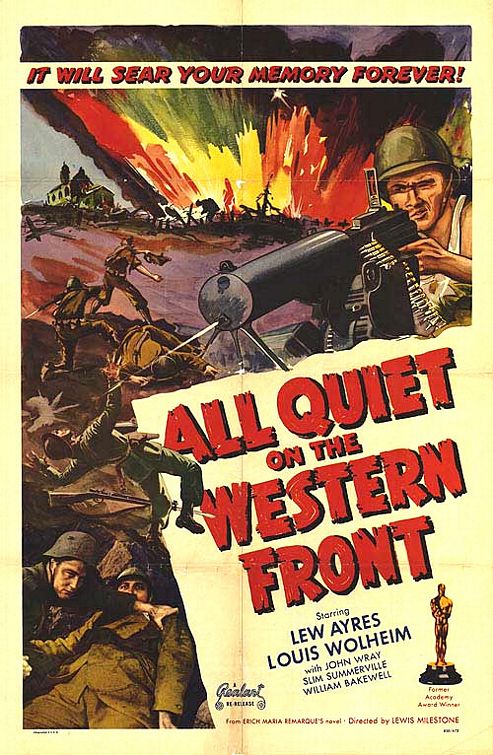

I’m always surprised by massive productions in early cinema, and the battlefield sequences here certainly qualify. An overwhelming number of men and weapons and explosions across a sprawling landscape, and they had no other option but to make it happen in front of the camera. That’s an amazing feat of logistics at any time even before you have to arrange to do it all safely, or at least safely enough that none in front of or behind the camera decide the pay isn’t worth the risk.

The card at the beginning provides a preamble about the purpose of this story not being to exonerate or condemn anyone but merely to document the generation destroyed by the war all the same whether they were killed or made it home. I suppose it’s mostly to assure English speaking audiences this isn’t a story about how the Allied Powers were the real bad guys and the Germans were the victims, but it could also be taken as “the old men that commit young men to die for inscrutable reasons aren’t the real enemy either”. It’s certainly easy to take that as a message, but I think the thesis is closer to the idea advanced when the soldiers are trying to figure out what the French did that was so terrible the Kaiser had to get into a war he didn’t want anyway: war is like a fever. Nobody wants it, but one day suddenly here it is. At the very least, the story seems to be saying that whose fault it is isn’t important, just it’s terrible and those who suffer the worst are the ones who had the least responsibility for it. I side more with the other guy who suggests that instead of conducting a war like how they’ve been doing it, all of the kings and ministers of the countries involved should be thrown into a field to settle their dispute with clubs.

I have the sense that while warfare was changing faster than anyone could keep up with it in the early 20th century and the first world war was possibly the cruelest war in history, stories like this in their day were kind of revolutionary for actually talking about what it’s like in the fighting, which was something that only the people who had been in it knew and talking about it was Not Done. Books and movies like this were the closest to being there that a lot of people could experience until news cameras started showing the public what was happening in the Vietnam conflict. So today it might be a little obvious to say that war is miserable, inhuman, and futile, but this was a message that much more needed to be delivered in its time. Even if it’s one we’re more familiar with now, it’s one that not enough seem to have learned.